-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Colleen L. Campbell, Sean McCoy, Nannette Hoffman, Patricia O'Neil, Decreasing Role Strain for Caregivers of Veterans with Dependence in Performing Activities of Daily Living, Health & Social Work, Volume 39, Issue 1, February 2014, Pages 55–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlu006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In response to the implementation of new Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) within the Veterans Administration health care system, the interdisciplinary nature of social work in health care settings is expanding to address emerging needs of veterans and their caregivers. One such area of expansion is the receipt of extended care services in the veteran's home environment. Social workers within PACT, also known as the patient-centered medical home, are tasked with movement of health care resources and care coordination centered around veterans in their residences. This presents social workers in the health care setting with new challenges for dealing with high burden and role strain for caregivers of veterans in noninstitutional settings who are dependent in performing activities of daily living. The current article establishes an approach, grounded in community science, for interventions within the Veterans Health Administration aimed at alleviating caregivers' role strain when caring for veterans with functional disabilities while optimizing implementation of home care and care coordination.

Veterans account for a significant portion of the population. According to the 2010 American Community Survey, there are over 21 million veterans currently living in the United States, accounting for over 10 percent of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). The primary service provider for this cohort of the population is the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest provider of health care services in the United States (Karlin, Zeiss, & Burris, 2010; Oliver, 2007). With a federally funded budget of over 43 billion dollars annually (U.S. Senate, 2011) and a service population over five and a half million veterans, the VHA is a driving force in creating innovative health care programs and services emulated by other health care providers nationwide (Miller & Intrator, 2012).

Caregiver burden is a significant social problem, being both an impediment to perceived quality of life and a detriment to caregiver physical and mental health (Papastavrou, Kalokerinou, Papacostas, Tsangari, & Sourtzi, 2007; Sussman & Regehr, 2009). The terms “caregiver burden” and “caregiver role strain” have been widely used within the gerontology field since the early 1980s and are interchangeably used in the literature to describe the negative reaction to the caregiver's social, occupational, and personal roles (O'Rourke, Haverkamp, Tuokko, Hayden, & Beattie, 1996). As defined by the VHA, a caregiver is a person related to or associated with a veteran over the age of 21 who provides routine care or assistance to the veteran in their home (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2011).

Studies have documented that chronic exposure to stress from caregiving results in poor quality of life, depression, social isolation, physical health decline, and psychiatric morbidities for the caregiver (Brodaty, Green, Hons, & Koschera, 2003; Czaja et al., 2009). High levels of caregiver burden are associated with patients requiring nursing home placement, recurrent emergency room visits, and frequent hospitalizations (Mason, Auerbach, & LaPorte, 2009). The literature supports the assertion that perceived caregiver burden is greater in instances in which the individual for whom caregivers are providing care has greater dependence in performing activities of daily living (ADL) (Razani et al., 2007).

Dependence in performing ADL has been defined by the World Health Organization (2001) through the creation of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF), to create a common language for discussing ADL. Within the fields of social work and health care, the ICF classifications are the main source of standardizing definitions and meanings of functioning and disability (Saleeby, 2011). Studies have shown that as individuals age and develop increasing frailty, they often experience decreased quality of life due to several factors, one of which is increasing dependence on others to perform ADL (Sixsmith et al., 2007).

Because of the negative outcomes of caregiver role strain and the impact on dependent aging individuals' quality of life, both the fields of social work and health care have emphasized research and interventions to address caregivers' burden and role strain related to performing ADL. Further, literature has shown that the existence of caregiver support programs significantly contribute to positive outcomes for both patient and caregiver (Spijker et al., 2008).

Veterans Health Administration Care Guidelines

The Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of (2011) imparted the VHA with a federal mandate to develop programs and interventions for veterans' caregivers to enhance caregiver well-being (VA, 2011; U.S. House of Representatives, 2009). The VHA is, therefore, currently implementing a wide range of innovative holistic programs aimed at enhancing both veteran and caregivers' emotional and physical well-being (Jha, Perlin, Kizer, & Dudley, 2003; Karlin et al., 2010). One area where such programs are being implemented is within the VHA Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) service line that provides veterans and caregivers with services in their home environment.

Home-based services are those where interdisciplinary health care team members visit with the patients in their place of residence (DeCherrie, Soriano, & Hayashi, 2012; Hicken & Plowhead, 2010; Mader et al., 2008). The residence may be a privately owned home or family member's home, an assisted living facility, or a rental apartment (Gill et al., 2002; Van Houtven, Jeffreys, & Coffman, 2008). VHA provides home-based services in all home settings, excluding nursing homes. A meta-analysis of home-based services by Weissert et al. (1988) found that while such programs vary in scope and benefits, the existence of interdisciplinary services is overarching and critical to the programs' successes. Interdisciplinary services are defined as those provided by a group of health professionals of multiple disciplines, enabling each group member to address their specific discipline's scope of services, thereby ensuring that patient care plans span discipline-specific services (Hughs et al., 2000; Stuck et al., 1995; Welch, Wennberg, & Welch, 1996).

Within the VHA, interdisciplinary teams include team members from medicine, nursing, social work, pharmacy, chaplaincy, pharmacy, psychiatry, psychology, and rehabilitation (Beales & Edes, 2009; VA, 2007b; VA, 2010). The VHA patient-centered medical home approach also embodies the interdisciplinary approach, albeit in the office setting as opposed to the home. The PACT core team is composed of a physician or midlevel provider, a nurse, and a medical support assistant, supplemented by social workers, pharmacists, and other mental health professionals.

Research within Social Work and Health care

The social work literature is replete with studies focusing on caregiver role strain and the impact of this social problem. A common theme is the negative consequences of caregiving on the caregivers' psychological well-being and the need for additional community services to address these concerns (Kadushin, 2004; Karlin et al., 2010; Keith, Wacker, & Collins, 2009). This is especially true for caregivers of chronically ill and medically complex individuals with dependence performing ADL, such as those served by the VHA system. Consistent with this theme is the importance of the caregivers defining themselves as such and their inclusion in health care planning for the patient (Ebenstein, 2005; Keith et al., 2009). As Ebenstein (2005) reported, through self-identification, caregivers are increasingly likely to use available community resources. The availability and use of formal community resources provided by health care professionals can serve as a social support for the caregiver, decreasing the negative consequences of caregiver role strain.

The health care literature is also extensive in its coverage of mental and physical health consequences in the caregiver who is experiencing high burden and role strain (Brodaty et al., 2003; Van Houtven, Oddone, & Weinberger, 2010). Studies have shown that providing support and assistance with ADL is crucial to illness management and promoting productive aging (Sixsmith et al., 2007). Using a community science approach, Sixsmith et al. (2007) indicated that placing a focus on ADL is key to enhancing the well-being of the frail. Thus the foci within the health care field are on enhancing medical management of illness causing the dependence, safety due to the dependence (Hain, 2012), and service coordination (Wheeler & Giunta, 2009).

Community Science

Both social work and health care interventions addressing caregiver burden are heavily grounded in community science (Ebenstein, 2005; Keith et al., 2009). Two approaches to community science, the ecological approach and typological approach, are useful in examining the relationship of the individual with dependence performing ADL and their caregiver (Monahan, 1993; Moore, 2010; Razani et al., 2007). The ecological approach to community science, pioneered by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1993) asserts that, to understand human beings, it is necessary to understand the physical environments in which they live. Whereas Bronfenbrenner's model was designed to explain childhood development, this model's extrapolations can be used to explore other phenomena such as an individual's social and health choices and the various levels of the social and familial systems' impact on individual development, decisions, and well-being (Moore, 2010).

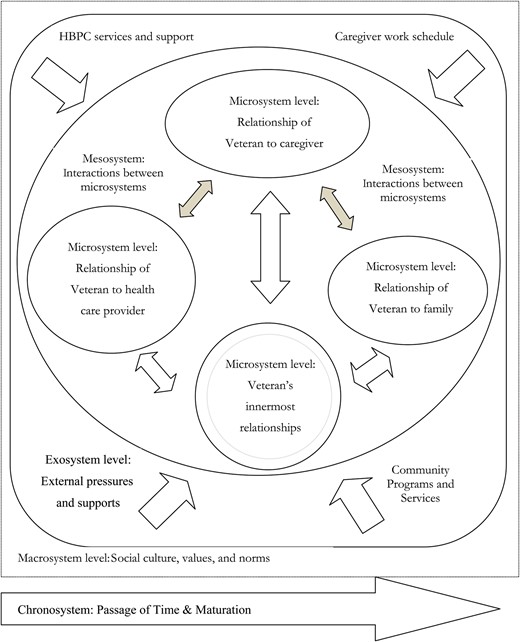

Within this model, there are five identified environmental layers: the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (see Figure 1). The microsystem is the layer closest to the individual, which would include the veteran's innermost relationships with the family, therapist, and allied health care providers, et cetera; relationships at this level are interactional (Moore, 2010; Paquette & Ryan, 2001). The mesosystem is the connections of the veteran's microsystems. Paquette and Ryan (2001) described the exosystem as the external events that impact the micro- or mesosystem, but through a unidirectional individual impact. The exosystem includes the existing resources supporting the veteran; although the veteran is not directly involved at this level, the exosystem can create a positive or negative influence on the veteran's development through adjustment to their dependence performing ADL through late adulthood and the end of life. The macrosystem, as defined by Bronfenbrenner (1993) comprises the culture, values, and norms of the larger society. Finally, there is the chronosystem, which involves elements of the passage of time and maturation occurring not only within the developing individual, but also within the course of the physical environment where the person lives (Bronfenbrenner, 1993; Paquette & Ryan, 2001).

The ecological approach to community science would support that community and organizational supports provide necessary social supports to enhance veteran and caregiver well-being (Wenzel, Glanz, & Lerman, 2002). Therefore, one could surmise that an intervention offering formalized social support to caregivers of the veterans with dependence performing ADL would decrease perceived caregiver role strain. The typological approach to community science includes disease-specific support group members, individuals with pervasive chronic mental health issues, individuals with similar chronic disabling health conditions, or those in a particular field of work such as nurses or hospital staff. This view of communities is consistent with the health care approach to caregiving and ADL, with the focus on disease-specific cohorts. When veterans develop dependence performing ADL, they become increasingly estranged from the community in which they reside, and they become increasingly disengaged. Consequently, the veteran may become progressively more dependent upon the individual caregiver, rather than on the available community and societal supports. A typological approach could explain the shift in reliance from the community to the individual caregiver, resulting in heighted burden and caregiver role stress. This approach makes it possible to understand the development and existence of caregiver role strain within this framework.

Development of an Interdisciplinary Approach: Social Work and Health Care

One of social work practice's main tenets is to provide quality of life and mental health services (NASW, 2008). Within the VHA, one of the main goals is to provide high-quality, patient-centered health care in a cost-effective manner (VA, 2007a, 2007b). Supporting community science utilization with this population of veterans is the common theme of providing supportive services, allowing the veteran to age in place, with the foundation of family and caregiver presence and involvement (Beales & Edes, 2009; Mader et al., 2008). It is, therefore, in harmony with the social work tenants and the VHA mission to employ a community science approach to providing community-based programs and services to decrease caregiver role strain, thereby facilitating veterans' and caregivers' perception of quality veteran-centered care (Nichols, Martindale-Adams, Burns, Graney, & Zuber, 2011). Moreover, health care utilization may be decreased, an important consideration in today's cost-conscious health care environment.

Currently, several VHA programs administered by social workers and health care professionals address the problem of role strain for veterans' caregivers. These programs' goals, consistent with a community science approach, are to offer additional support and resources to the caregiver, thereby decreasing their perceived role strain and stress (Nichols et al., 2011; Wray et al, 2010). However, most are limited in scope to telephone interventions or provide only for disease-specific groups (Nichols et al., 2011; Riopelle, Wagner, Steckart, Lorenz, & Rosenfeld, 2011; Wray et al., 2010). While telephone interventions and support have been found to be both cost-effective and efficient, the efficacy level of such programs in decreasing caregiver burden has not reached that of home delivery programs (Wray et al., 2010). As for the home-based programs designed to support caregivers, within the VHA the majority of home-based programs that support caregivers tend to be disease specific, such as providing services only to caregivers of veterans who have experienced a stroke, terminal illness, or dementia (Riopelle et al., 2011).

Within the VHA, one exception to these limited-scope or disease-specific programs is HBPC. Under the GEC program umbrella, HBPC is the long-established evidence-based VHA program that offers home-based interdisciplinary interventions and services to veterans and their caregivers (Beales & Edes, 2009; VA, 2007b; Johnson, 2004). As a result of its community science–grounded approach and focus on the person-in-environment, the Federal Advisory Committee (1998) report on the future of Veterans Administration Long Term Care noted HBPC to be a unique program providing longitudinal primary care services in the home setting.

Home care services use a significant portion of the VHA budget; the VA spends over 7.5 percent of its budget on home-based care (Kizer & Dudley, 2009). As such, multiple studies conducted on these programs have overwhelmingly demonstrated that the VHA HBPC program provides cost effective veteran-centered care, enhancing both veteran and caregiver perceptions of well-being (Chang, Jackson, Bullman, & Cobbs, 2009; Edes, 2010; Hicken & Plowhead, 2010; Spijker et al., 2008). Additionally, studies have documented a clinically significant positive impact of these services on veterans' health, as a result of preventing institutionalization and decreasing caregiver burden (DeCherrie et al., 2012; Hughs et al., 2000; Johnson, 2004; Mader et al., 2008; Van Houtven et al., 2008; Van Houtven et al., 2010).

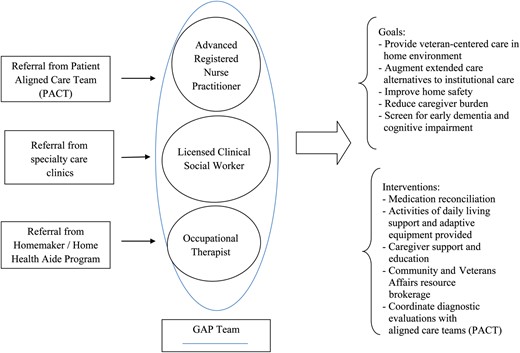

While HBPC provides social support at the exosystem and macro system levels, and aims to decrease caregiver stress through enhancing the attractiveness of a shift toward a Gemeinschaft society, such a program does not meet the needs of all caregivers for veterans with dependence performing ADL. As such, there existed a service gap whereby there were no formal home-based program services supporting caregivers and veterans who are dependent in performing ADL but not HBPC enrolled. Thus, in December 2011, the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) initiated a unique pilot project, the Geriatric Assessment Program (GAP) Home Assessment Program (Campbell, 2012; O'Neil & Campbell, 2012).

GAP is funded through fiscal year 2013 within the NF/SGVHS by a Veterans Administration Central Office Long Term Non-Institutional Care T-21 GEC grant. GAP was developed to augment extended care alternatives to institutional care, delivering quality patient-centered home health care services to veterans to bridge the gap between the care provided by their PACT providers and their home care needs (Hoffman, 2011b). The program targets veterans who are not HBPC enrolled and are dependent in performing ADL, as evidenced through their receipt of, or referral to, the VA Homemaker/Home Health Aide Program (H/HHA) (Campbell, 2012; O'Neil & Campbell, 2012). As of 2012, the NF/SGVHS had more than 300 of 800 veterans enrolled in the H/HHA program who did not receive HBPC, and this number has grown significantly since fiscal year 2005 (Hoffman, 2011a).

GAP program services entail the receipt of interdisciplinary home visits by a nurse practitioner, occupational therapist, and social worker for those non-HBPC veterans receiving H/HHA services to identify unresolved medical, social, safety, and environmental needs that cannot be detected during a primary care clinic visit (see Figure 2) (O'Neil & Campbell, 2012). One of the goals of this innovative holistic home care service is reducing caregiver burden (Campbell, 2012). This goal is in concordance with the Veterans Administration Medical Centers and Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) strategic planning mission of fostering a “veteran centric cost effective organization” (VA, 2008b). As funding is based on the success of program outcome measures, it is of significant benefit to conduct research to demonstrate program success in decreasing caregiver burden. Furthermore, as promoting caregiver well-being and aging in place are part of the VHA's strategic planning mission, knowledge that the NF/SGVHS has successfully addressed the issue of caregiving would be of benefit to other VISNs—by providing education regarding successes of the GAP program—implementing similar programs with veterans in other service areas.

As previously reviewed, the literature clearly supports the affirmation that home health care services with indefinite duration, such as those provided by the VHA HBPC program, are effective in providing increased quality of life and enhancing caregiver perceptions of well-being. However, there is a paucity of literature to support the assertion that a time-limited home-based interdisciplinary intervention program modeled after HBPC would have a similar impact. The GAP program is a newly piloted program and is unique to the NF/SGVHS. There has never before been the opportunity to examine the impact of such a veteran-centered home-based service of a time-limited scope and the impact of such services on perceived caregiver burden.

Conclusion

In summary, this article offers a review of the significance and impact of caregiver role strain within the fields of social work and health care, with a specific focus on caregivers of veterans who are dependent in performing ADL (Kadushin, 2004; Karlin et al., 2010; Keith et al., 2009). Role strain for caregivers of veterans with dependence performing ADL is a problem that can be well understood by making the most of community science ecological and typological approaches (Ebenstein, 2005; Monahan, 1993; Moore, 2010). An area for future research to study these phenomena is offered within the interdisciplinary services provided by the VHA. Research specifically examining the NF/SGVHS GAP program is suggested to explore the efficacy of a home-based time-limited interdisciplinary program and the impact on role strain for caregivers of non–disease-specific groups of veterans with dependence performing ADL.